Jewish News 31 October 2024

A Drawing is Worth a Thousand Words

Jenni Frazer finds a book on cartoons related to Britain, Israel and Palestine tells us much about our own history.

Sometimes the great political cartoonists can create, in a simple drawing and caption, the most intelligent commentary on the issue of the day. Such cartoons are often funny - to the same degree as they are savage - and get to the essence of a gaffe more speedily than the thousands of words accompanying them.

One thinks of some of the hideous and scatalogical manifestations of Boris Johnson, a cartoonist's dream, or the merciless depiction of John Major with his underpants over his trousers, the latter an image first created by Steve Bell, but which became so pervasive as to be the defining view of Major's premiership.

For present-day readers the cartoons don't need much explanation as we are familiar with the protagonists and the political issues. But as a way of learning about history, a deep dive into contemporary commentary is necessary.

In his delightful and informative new book Drawn To The Promised Land, Dr Tim Benson, Britain's leading authority on political cartoons, walks the reader by the hand as he explains the background behind scores of cartoons from 1917 to 1949. For this book is a specific look at the fractured history of the Jews and their ultimately successful attempt to re-establish their foothold in the land of Israel, while being thwarted by the Great Powers and, particularly, the British Mandate of Palestine.

Two completely artificial figures stand out in these cartoons - the metaphorical creations of Uncle Sam for the United States and John Bull for Britain. Both Sam and John appear in numerous drawings, used by the cartoonists to denote the national feelings of both countries. Sometimes Benson even offers us Uncle Sam and John Bull in consultation.

Another recurring theme used by many of the cartoonists is the story of King Solomon and his attempt to define the real mother of a baby by decreeing that the infant should be sawn in half and each half given to the two squabbling women - styled, often, as Arabs and Jews - trying to claim him. The horror-stricken real mother gives up her claim after Solomon's ruling: but it's hard, looking from today's perspective, to see any such solution applied now.

There are gems in this collection: drawings in Punch by Ernest Shepard, for example, who later became famous as the man who drew the definitive Winnie The Pooh. Or American cartoons by Theodore Geisel, another artist who achieved world fame as Dr Seuss, the author and illustrator of well-loved children's books.

Some of my favourites, however, are from long-defunct newspapers and by men- for some reason they are all men - who did not become household names. But, good heavens, are they sharp. Take, for example, George Whitelaw in the Daily Herald, in June 1945.

We see a British ex-squaddie outside parliament, looming over a tiny figure clutching a paper on which is written, "Anti-Jewish Plan". This, it turns out, was the mercifully now-forgotten Tory MP for Peebles, Captain Archibald Ramsay. Benson tells us that he had wanted to "reintroduce the medieval Statute of Jewry, which was repealed in 1846. The statute made the wearing of a yellow star compulsory and denied Jews social intercourse with Christians. Ramsay's motion said the statute 'protected His Majesty's subjects from Jewish extortion and exploitation"". Whitelaw's caption reads simply: "For This I Fought Hitler?" To a British readership just waking up to the horrors of the Holocaust, this must have resonated. To a present-day reader, aware of the conspiracy theories abounding on social media, there is a disturbing resonance, too.

Some of the most provocative cartoons are by Jewish artists such as Berlin-born Victor Weisz, better known as Vicky, who drew for the Spectator and eventually the News Chronicle after being interned on the Isle of Wight when war broke out in 1939. Benson makes the shrewd point that when it came to attacking the British government over its "closed-door" policy to the remnants of European Jewry trying to get into post-war Palestine, the Jewish cartoonists became more reticent, as they did not want to appear special pleaders, focused on only one issue.

But that was in Britain: cartoonists in America, even when, like Arthur Szyk, they came from Europe, were much more outspoken.Benson tells us that Szyk believed that "all cartoonists should speak out against Nazi tyranny". He quotes Szyk, whose mother died in a camp in Poland in 1942, writing: "An artist, especially a Jewish artist, cannot be neutral in these times." Szyk, who had fled Europe and settled in New York in 1940, "contributed a steady stream of anti-Nazi cartoons" for the New York Post.

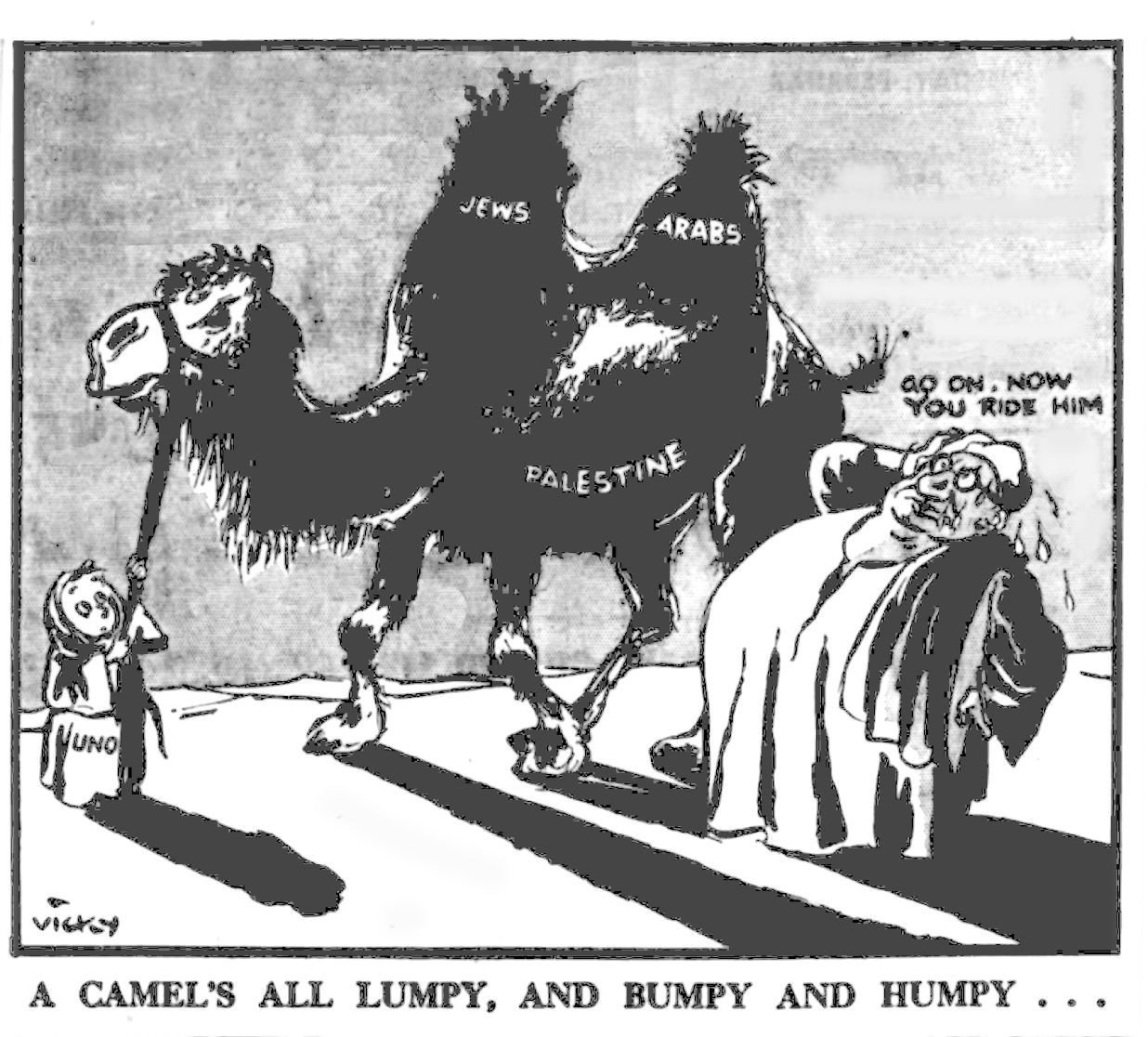

But there is a wonderful Vicky cartoon captioned "A camel's all lumpy, and bumpy, and humpy", showing a sweating British foreign secretary Ernest Bevin being told by the United Nations: "Go on, now YOU ride him," as he views the twin humps labelled "Jews" and "Arabs" of a camel called Palestine.

Sometimes Benson provides contemporary political commentary from newspapers other than the cartoons he shows. An October 1945 cartoon, for example, is by another Jewish cartoonist, Eric Godel, in America's PM magazine. It shows a figure representing western civilisation' telling what is presumably a Jew behind barbed wire that "we'll do everything possible to save your life". But the man says: "It's not just my life that's at stake, it's also your soul." To accompany this, Benson quotes a Daily Dispatch report about Dr Alexander Altmann, communal rabbi of Manchester and Salford, protesting at the "shocking" living conditions of displaced Jews who had been liberated in Europe. "These unfortunate human beings have been liberated, but for them there is no liberation," Dr Altmann wrote. Benson tells us that Dr Altmann's own parents were murdered in Auschwitz. I did not know this: in my home, he was known mainly as one of the rabbis who married my parents.

The truly striking thing about this book - which Benson has dedicated to his great-great-grandfather, Peysach Czyzyk," who was orphaned at the age of three as a result of a Russian pogrom" - is the numerous cartoons that echo the present day. Perhaps one of the most striking images is a cartoon from July 1946, drawn by Leslie Illingworth and published in the Daily Mail.

It was printed just after the news of the bombing of Jerusalem's King David Hotel by right-wing Jews. Illingworth shows us, among the rubble, two British soldiers carrying a stretcher on which there is a cloth bearing the words "World Sympathy Zionism". It could not be closer as an image to the picture of Israeli soldiers taking a stretcher with the body of the Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar out of the rubble of Rafah.

A picture is worth a thousand words, it is often said. On this reading, Tim Benson has done us a great service, breaking down a complicated and still-disputed history into more easily assimilated images. Such a smart book.

• Drawn To The Promised Land, A Cartoon History of Britain, Palestine and the Jews 1917-1949 by Tim Benson is published on 28 November by Halban at £14.99

Victor Weisz ‘Vicky’, News Chronicle, 25 February 1947

Eric Godal, PM magazine, 2 October 1945

George Whitelaw, Daily Herald, 6 June 1945

Theodore Geisel (Dr Suess), PM magazine, 18 September 1941